In a sense, Patricia Russell was well-suited to a creative life because her early years were already chronicled in public. She and her sister Susan Hudson Russell were ersatz Akron, Ohio celebrities, granddaughters of M.M. Kindig, a lifelong president of the Burger Iron Company, whose parents John & Ruth were frequently in the society pages until their untimely deaths in 1966 and 1968, respectively. Their births, notable public appearances, and the loss of their parents were reported in the local papers. Susan became both a collector of art and a consultant to others investing in purchasing it, working during the '70s at the NEA. Patricia in turn obtained a B.S. in psychology and dramatic arts from University of Wisconsin, and was seeking acting roles for a decade until switching to directing, receiving a Master's degree from NYU in 1973. Both sisters had entered marriages in their early adulthood that proved short-lived, and even their activities post-divorce were given column space.

During her time at NYU, Russell made a short film geared for the educational market, SALLY, about a 13-year-old facing the vagaries of puberty: getting taunted by older girls (including her sister), uncomfortable health classes, and learning about her own body. Film historian and Trailers From Hell contributor Glenn Erickson described it in 2003 as, "This is the keeper...[starring] a phenomenally sympathetic actress named Irene Arranga....[this very] effective film would surely reach girls in the right way." Arranga would later touch TV viewers in the last season of the sitcom "WELCOME BACK KOTTER" as Arnold Horshack's girlfriend Mary, whom he would wed in the series finale. SALLY took an unsually long time to reach the market, being serviced to schools in 1979, and according to chroniclers of educational films, was little screened to the very audience it was geared for, due to teachers and other authorities displeased with the ambiguous and non-judgmental tone of the story.

Russell's vivid feelings about her brief marriage provided the foundation for her sole feature film, REACHING OUT. It is a loosely autobiographical story of a young wife with ambitions beyond homemaking that are treated condescendingly, who grows discontent with being regarded as a trophy for her social climbing husband, especially after she catches him cheating on her. She leaves him to move to Greenwich Village, where she must navigate the satisfaction of following her acting dream with the dangers of being a single women, including an attempted rape. Mixing funds raised from supportive investors with the remains of an inheritance from her grandfather, she amassed $500,000 and began shooting the film in 1974 over the span of two and half years. Then after completion, she spent another two years trying to get it shown. She was able to enter it into the first Utah/U.S. Film Festival in Salt Lake City, later to be known as Sundance, in September 1978, where it was in competition with Claudia Weill's GIRLFRIENDS, Penny Allen's PROPERTY, Mark Rappaport's LOCAL COLOR. George A. Romero's MARTIN, Martha Coolidge's NOT A PRETTY PICTURE, and Paul Mazursky's NEXT STOP GREENWICH VILLAGE.

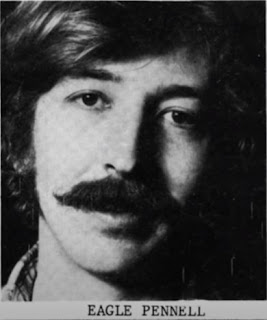

Most fatefully, it also put her in the orbit of Austin, Texas filmmaker Eagle Pennell.

"Eagle Pennell was politely called a regional filmmaker by those unaccustomed to his kind, and like many in his native Texas, he had an outsized impression of his own identity that ultimately destroyed him. In 1978, when A-list Hollywood was made up of veterans of Roger Corman’s shoestring epics, and everyone else in America with dreams to burn now worked for Corman to replace them, the first inklings of what we now think of as independent film came courtesy of people who were too clueless or inept to follow that simple protocol. One of them was Eagle, whose shaggy dog buddy comedy THE WHOLE SHOOTIN' MATCH pioneered that Austin-specific sort of epic underachieverdom that SLACKER later turned into an anthropological treatise. But Eagle’s laconic dreamers, drunk as a lord and impossibly balanced on the thin line that separates ambition from nostalgia, were more than just literary conceits. They were Eagle in a nutshell." - Paul Cullum, "A Tribute to Eagle Pennell", Arthur Magazine, October 2002

Pennell had conceived THE WHOLE SHOOTIN' MATCH from reworked elements of a previous short film, HELL OF A NOTE, and with collaboration from neophyte writer/producer Lin Sutherland, shot it for approximately $30,000 with friends and favors through 1977. It drew enough positive attention from its play at the USA Film Festival in Dallas that it was acquired by New Line Cinema, then known more for foreign and arthouse films than for the horror classics that made them world-famous in the '80s. But its most significant elevation came when the film drew the attention of Robert Redford, who as the primary muscle behind the nascent Sundance festival, felt Pennell was the kind of under-the-radar talent whom such an event could nurture and promote. THE WHOLE SHOOTIN' MATCH would be touted in 1981 by Gene Siskel & Roger Ebert on their original "SNEAK PREVIEWS" review show on PBS as an independent to watch, in an episode that also featured John Sayles' RETURN OF THE SECAUCUS SEVEN, Richard Pearce's HEARTLAND, Anna Thomas' THE HAUNTING OF M, and Victor Nunez' GAL YOUNG 'UN.

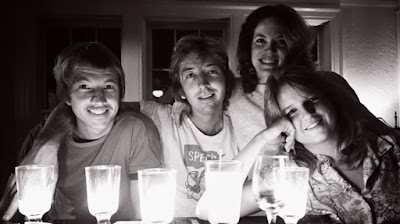

As recounted by author Alison Macor in her book CHAINSAWS, SLACKERS, AND SPY KIDS: THIRTY YEARS OF FILMMAKING IN AUSTIN, TEXAS, Pennell's film had won a "special second prize" from the Utah judges (First Prize went to Claudia Weill's GIRLFRIENDS), and at a post-ceremony after-party, amidst engaging in the kind of braggadocious antics that would become his trademark, Pennell and Russell became more than friends that evening. Russell spent the following year of 1979 attending more festivals and one-off screenings with REACHING OUT, plus four-walling an April test release in Austin, with a goal to secure it a distribution deal. At least once, she traveled in tandem with Pennell and SHOOTIN' MATCH: they were both programmed at the first Independent Feature Film Market in September 1979, along with their previous U.S. Festival rivals PROPERTY and NOT A PRETTY PICTURE. While never mentioning his name in subsequent interviews of the time, she acknowledged that she had recently become an unexpected mother, and was planning to write her next script about that experience. Meanwhile, Pennell, to the best of available research, never mentioned her name in any documented fashion, but did sit for a photo in 1980, taken by his photographer friend Ard Hesselink in Venice Beach, in the company of Russell and their son. As Hesselink observed when he posted the photo to his website and Flickr accounts after Pennell's death, he described their child having been conceived "more or less by accident," and after moving out of America, maintained contact with Pennell, but learned no further information about Russell or their son. It is likely the parents ceased any pretense of being a couple shortly after this photograph was taken.

Despite collecting good reviews from both Hollywood royalty as Robert Wise and respected indie pioneers as Robert M. Young, along with praise from Stephen Farber and Roger Ebert, by the '80s, Russell still had not found a willing distributor, and ultimately paid out of pocket to open REACHING OUT in New York City in May 1983. It was not received well. An absurdly hateful review in the New York Daily News called it "shameless Me Generation indulgence." And the ostensibly polite Janet Maslin of The New York Times seemed personally offended, as she dismissed it as a "lifeless, amateurish chronicle" and described her character as a "not very sympathetic young woman" and "a whiny, self-pitying victim." Talking to the White Plains Journal News a year later, Russell remarked, "The morning the review came out was like a funeral at my ad agency. They all knew it was the kiss of death to an independent film. I kept hoping the audience would still come, but a week later, I was given a four-day notice by the theater owner, breaking our contract." Aside from some initial cable TV airings after the NYC run, a placement as the only American film at the 1985 San Sebastian International Film Festival in Spain, and a revival presentation at the 1993 IFFM which put it in concert with newer independents as diverse as Haile Gerima's SANKOFA and Kevin Smith's CLERKS, REACHING OUT would not play commercially in any further cities, enter TV syndication, or be issued on any physical media. And while she made some later attempts, she would not direct another feature film after.

Pennell's trajectory after his interlude with Russell delivered a more prolific body of work, but also delivered more difficulties and tragic results that, as even his closest friends would admit, were caused by his own hand. He had earned a development deal with Universal that brought him to Hollywood for two years, but he reportedly did nothing under their aegis but fuck around and find out, He returned to Austin and made another film on a shoestring budget, LAST NIGHT AT THE ALAMO, that was also greeted with critical acclaim - Janet Maslin called it "a ribald and faintly mournful chronicle" and glowingly described how all its characters "all join in cursing, drinking, carousing and otherwise preparing themselves for imminent disaster." Though it also got a substantial expansion from respected distributor Cinecom, it didn't propel him much further than SHOOTIN' MATCH had. After a poor experience directing ICE HOUSE, a vanity project for actor Bo Brinkman and his then-wife Melissa Gilbert, he made two more micro-budgeted films, HEART FULL OF SOUL and DOC'S FULL SERVICE, that did not win the praise or attention of his previous influential features, nor any sort of constructive theatrical play. Amidst this slump, he was descending further into alcoholism and erratic behavior. He became frequently homeless and itinerant, attempting sobriety to little progress, and getting assistance from a dwindling body of enablers. Pennell died in Houston, Texas, a week before what would have been his 50th birthday, on July 21, 2002.

Patricia Russell significantly altered the priority of her life from being an artist (though she was still writing scripts and attending screenings in Los Angeles) to being an advocate for enlightened and humane treatment of mental health in society. Her motivation came from observing her son by Pennell - who, though regularly publicly named in newspaper interviews and on her Facebook posts, will not be identified here to respect his privacy - struggling with the similar troubles of mood swings and substance abuse that his father was notorious for. In a 2007 website profile she wrote for the Ventura County branch of NAMI, she elaborated:

I don’t know what my life would be like today if I had not found out about NAMI in 2001. A friend of mine, who knew the roller coaster in hell I had been on dealing with my son’s co-occurring disorders of addiction and Bipolar disorder, told me that I should take NAMI’s Family to Family class. I took his advice and was transformed by the experience!

I learned about his disorders, possible medications, treatment, etc. but most importantly I learned how to become an advocate for my son. I became a fighter to get my son the services he needed to literally survive! I attended the care and share meetings and gained strength and hope from the acceptance and understanding I received. If it wasn’t for our group’s leader, who was there for my son and me during many life-endangering crises, I honestly believe that the outcome would have been different. There are miracles that occur when like-minded loving people come together to be of service. This is what NAMI does.

Last year I became a NAMI Board member because I want to give back. My life work has been in the film industry as an independent filmmaker. I believe in telling stories that inspire the audience. I have been fortunate to be involved with incredibly talented people as a producer. I also have made my own films, including a feature film called REACHING OUT. I taught myself digital filmmaking and editing because I believe that this gives us the opportunity to tell these stories. I produced a 17-minute video of the first NAMI Walk in 2006, and I’m editing NAMI Walk 2007.

My son, after seven years of crisis after crisis, has been stable for nine months, holds a job, takes classes, has a sponsor, is part of a spiritual community and is pursuing his dreams. I can’t say enough about NAMI!

Her NAMI activities yielded her an award for "Family Mental Health Advocate of the Year" by the Los Angeles Mental Health Commission, and served under former Los Angeles D.A. Jackie Lacey on her Criminal Justice Project workgroup for three years, leading to the creation of diversion programs being made available for people who have committed low-level crimes in lieu of incarceration. The sole occasion where REACHING OUT was publicly screened in the noughts was presented by the DMH Service Area Two for "May is Mental Health Awareness Month," held at the Harmony Gold screening room on June 15, 2018.

The only readily available public comment Russell made about Pennell after their breakup was posted on June 12, 2012, as a comment on the Arthur Magazine website reprise of Paul Cullum's elegy for the artist. She wrote:

"This piece on Eagle really captures him. I’m feeling many emotions. This is brilliant writing. I met Eagle at the US Film Festival in 1978. Eagle is the father of my 33 year old son...My son has so much of Eagle in him. Currently he is in the Hospital. The last time my son and I saw him was in 1987. He came to visit [and] gave him a basketball. I took a photo of them."

In a 180° switch from having her birth and childhood reported by the local press, Patricia Russell died on December 2, 2021 in mostly quiet anonymity; while there were Facebook posts from her friends about the passing, no published obituary or registered resting place has been found in my research. In the ten years that she maintained a Facebook account, she never mentioned Pennell in any fashion, but constantly wrote loving and positive updates about their son, posting photos of him looking content and the spitting image of his father. He does not use social media, so his current whereabouts are not known: fates willing, he is healing and healthy and adjusting to living life without his devoted mother.

While Russell's lack of acknowledgement of Pennell can be understood and accepted as personal reticence, the near-silence about Russell from the community of friends and film writers who have kept Pennell's life and career in discussion disturbingly feels like wholesale erasure. She was never mentioned in Paul Cullum's essay. She was never mentioned by The Austin Chronicle in any of the testimonies gathered when the publication eulogized him. For a particularly stark example, the 2008 documentary THE KING OF TEXAS, directed by Pennell's nephew René Pinnell, provides an ostensibly thorough warts-and-all portrait of the filmmaker, talking to family members, actors, writers, and others about his life. Several examples of his cartoonishly cavalier antics are brought up, including one particularly icky incident at his 1983 wedding involving his new sister-in-law. It makes a laudable effort to not engage in easy hagiography about its subject. However, neither Patricia Russell, or the son Eagle fathered with her, are ever mentioned.

I could understand that perhaps in the matter of Patricia, since their relationship was brief and he probably never talked it up much, many of the interviewees hadn't any good anecdotes or insights about her to share - maybe some didn't know about her at all. However, according to the aforementioned historian Alison Macor, Russell did keep in contact with the rest of the Pinnell family, so they would have known about her, and, importantly, the child of his she raised. And I'll go a step further and be willing to consider that Eagle's relatives maybe wanted to not bring too much unwanted attention to a private individual who had little contact with his father. But not even acknowledging that he had a son to begin with...to put it in Texas parlance, that's an omission as serious as the business end of a .45. Since this documentary ultimately exists to pitch the artistic worth of Eagle Pennell to new generations, an impression is left that its producers felt the unfamiliar viewer could sit still for a man bent on self-destruction with a pattern of treating women and collaborators shabbily, but not cotton to a deadbeat dad.

For what it's worth, though not identified, Patricia can be seen briefly in the film, in this photograph shown during the segment on the production of THE WHOLE SHOOTIN' MATCH.

I am not here to call out Eagle Pennell, pass some moral judgment on him, or devalue his body of work. There are plenty of artists with regrettable life choices in their personal ledger whose creations I find vital and worth preserving and sharing. I have never seen any of Pennell's films. And I have never seen Patricia Russell's REACHING OUT. As such, divorced from any truthful way of arguing whether any of these movies achieve or fail at their intended message, let us simply contemplate the following. Pennell, as memorialized by the very people who loved him and preserve his legacy, wasted several opportunities, burned bridges, and yet still was able to rustle up the means to create several films to be remembered by. Whereas Russell, who did start out with some more advantages that Pennell (and probably better people skills), and for a short interval stood on an equal footing with him as an independent filmmaker to watch, only got one grasp at the Big Brass Ring. And that opportunity was cut short by bad reviews for her film...from one engagement in one city. And despite her best efforts, could not rally the kind of interest her former partner commanded to mount another production. All the while, having the additional burden of taking care of the largest mess that he, as a lifelong mess-maker, left behind. We will never know if Russell could have been the Camille Claudel to Pennell's Auguste Rodin. What we do know is he got multiple second chances, and she barely got a first.

The ideal adjustment to balance this particular inequity would be to pull REACHING OUT from the limbo it sits in, and for an innovative film programmer, physical media label, or streaming platform (or hey, why not all of the above) to assist in getting it back into circulation, so it can be appraised by a larger and more thoughtful body of viewers than it found on its previous too-brief release. I am hoping either her son or extended family, as part of her estate, have seen fit to keep the elements safe. Perhaps it will be better received. Or maybe it will still be met with a shrug, Either way, Pennell's CV will still have the higher profile, but maybe those films he made after his time with Russell could be analyzed with a new and interesting context.

Writing at length about a woman you never met, who directed a movie you never saw, to elevate her to an audience you don't know even exists, well, that's kind of a fool's errand. But then, this is the story of a woman who found herself effectively bound for life with someone who, in the parlance of Neil Diamond, was a fool who dreamt of being a king, and after an ignominious death, became one. Why shouldn't she have another fool like myself acting on her behalf?

Patricia Ann Russell

June 10, 1943 – December 2, 2021

.jpg)